The Fantasy Coffins of Ghana: History, Meaning, and Cultural Significance

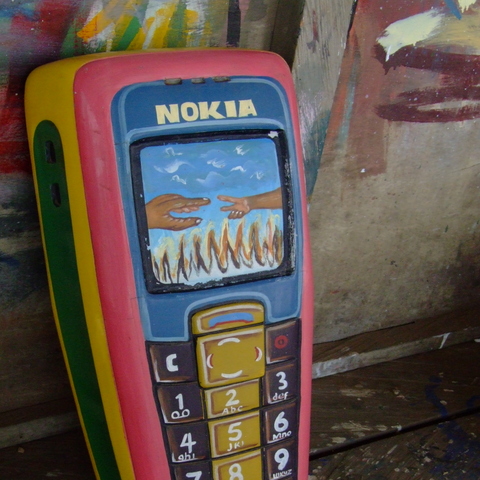

The fantasy coffins of Ghana, also known as figurative coffins or abebuu adekai (meaning "proverb boxes" in the Ga language), are one of the most fascinating and visually striking expressions of contemporary African art and traditional culture. These elaborately crafted coffins, shaped like animals, everyday objects, vehicles, or symbols, are created to honor the deceased and celebrate their life, profession, status, or dreams. While they are internationally recognized today as works of art, they are deeply rooted in Ghanaian traditions, especially among the Ga people of the Greater Accra Region.

Explore Fantasy Coffins - 3 Top Tours

Origins and Historical Background

The tradition of figurative coffins is believed to have emerged in the 1950s in the Ga community, particularly in Teshie, a coastal town near Accra. The origins are often credited to a carpenter named Seth Kane Kwei, who is said to have created the first figurative coffin around 1951.

The story goes that Kane Kwei originally made a cocoa pod-shaped palanquin (a ceremonial carrier) for an elder, who died before it could be used. Rather than let it go to waste, the palanquin was used as a coffin. This inspired others to request similarly creative coffins that reflected aspects of the deceased’s life. Over time, this practice grew in popularity among the Ga, who already had cultural traditions that supported elaborate funeral rites and symbolic representation of status.

Cultural Context and Symbolism

In Ga culture, funerals are major life events, often more important than weddings or birthdays. They are celebrations of life, and the funeral is not only about mourning but also about honoring the deceased’s legacy. The fantasy coffins serve both as tribute and status symbols, meant to reflect the profession, interests, achievements, or personality of the deceased.

For example:

A fisherman might be buried in a fish-shaped coffin.

A teacher might receive a book- or pen-shaped coffin.

A wealthy person could be buried in a Mercedes-Benz-shaped coffin.

A farmer might be laid to rest in a chicken, maize, or cocoa pod coffin.

These coffins often serve as visual metaphors or proverbs — hence the term "abebuu adekai." They communicate messages about the individual’s life or values in symbolic form.

Craftsmanship and Artistic Recognition

Fantasy coffins are handcrafted from wood, often painted in bright, eye-catching colors. The designs can be incredibly detailed, requiring weeks or even months to complete. The workshops, especially in Teshie and nearby Nungua, have become centers of artistic innovation, with the skills passed down from master craftsmen to apprentices.

What began as a local tradition has gained international attention. Fantasy coffins have been exhibited in art galleries and museums around the world, including the British Museum, the Brooklyn Museum, and the Centre Pompidou in Paris. Some coffins are now made exclusively as art pieces, never intended for burial.

Notable coffin designers such as Paa Joe, a former apprentice of Kane Kwei, have become internationally celebrated artists in their own right. Paa Joe’s monumental and symbolic coffins have been displayed in Europe, Asia, and the United States, often as commentary on death, power, and cultural heritage.

Modern-Day Relevance

While the tradition remains strong, especially among the Ga people, not all Ghanaians use fantasy coffins. The practice is more common among those who can afford the high cost (which can range from several hundred to thousands of dollars), and among those who wish to honor traditional values or make a bold cultural statement.

Fantasy coffins continue to be used in actual funerals today, particularly in Teshie, Nungua, and La, and are part of Ghana’s growing cultural tourism industry. Visitors to Accra can tour coffin workshops, meet the artists, and witness firsthand how art and tradition blend in one of Ghana’s most unique cultural exports.

A Story of Life, Death and Culture

The fantasy coffins of Ghana are much more than artistic curiosities. They are powerful expressions of identity, creativity, and respect for the dead. Rooted in Ga customs but recognized globally, they show how traditional African beliefs can adapt and thrive in the modern world. Whether seen in a village funeral or a museum in Europe, each coffin tells a story — not just of the person inside, but of a culture that celebrates life even in death.

3 girls selling fruits and food at the road side. (c) Strictly by Remo Kurka (photography)